7. Adventures in Eastern Europe

The second phase of the Grand Tour Préhistorique had begun. For this stage, which would last around two weeks, I looked for a place to stay somewhere in the middle of a triangle—three cities, each boasting a relevant museum: Vienna, Brno, and Bratislava. These cities were only about an hour and a half apart from each other, and, conveniently, each lay in a different EU country. With that in mind, I could add three international institutions to my list of partners in one go, which would be useful for future funding applications. Since I was traveling on a tight budget, my goal was to find a farmer living somewhere inside this triangle who wouldn't mind letting me camp on his land for free. I ended this phase with a few days in the beautiful city of Ljubljana.

Eastern Europe has much to offer from the Stone Age—not cave paintings this time, but rather a remarkable collection of graves and objects. The phase began in Prague, where I spent a few days exploring the city with a friend. There, at the National Museum of the Czech Republic, there was an exhibition on human evolution with a major attraction: People and Their Ancestors featured the bones of Lucy, on loan from Ethiopia. The remains of this 3.2-million-year-old hominin had, in the 1970s, profoundly changed our understanding of human evolution. Lucy walked upright, still ate mostly plant-based foods, and used very simple stone tools.

That description may sound a little dry, and at first, when I stood before her, I felt as though I were simply looking at bones. But through the lens of the archaeologists who studied them, those bones stood for something much larger. Lucy helped reconstruct the grand narrative of humankind: the invention of tools, the taming of fire, the emergence of complex spoken language, the waves of migration that peopled every habitable part of the planet, and the diversification of human species—of which we alone remain. Within that vast epoch, there were millions of small stories; Lucy had one, and I, too, will tell one in my film.

After Prague, I spent a few days in a bunker-turned-Airbnb in the wine region south of Brno. I was perfectly situated in the middle of my triangle, yet something still felt off. As much as I loved the landscape, I struggled to connect with the Czechs. In the countryside, hardly anyone spoke a word of English or even German, and despite phone calls with friends, I began to feel somewhat isolated after a few days.

One of the few moments of real communication came during a walk, when I sat under an oak tree on a hill and a few retired cyclists stopped to rest. We looked out over a wide, rolling landscape—villages in the distance, mountains beyond them, and between those, colourful fields curving with the terrain. With about ten words of English, one of the old men asked where I was from and what I was doing there. "Holland," I said. "Archeologica." They responded enthusiastically and pointed toward one of the villages in the distance—it turned out to be Dolní Věstonice, the world-famous Paleolithic site that had drawn me to the region in the first place.

I had seen on the map that Dolní Věstonice was nearby, but coming from my flat home country, I wasn't used to being able to see another town just like that. The spaciousness of this hilly landscape fascinated me. Without realizing it, I had been looking out over the valley where mammoths once roamed—and where the people whose graves still astonish us today once hunted them.

But that was as far as my local contact went, and so I decided to cross the border. By then, my German was decent enough that I could speak to people more easily in Austria. Here's how it went. I picked a spot on the map where I thought I might find a farmer. I knew nothing at all about Niederösterreich, so I decided to choose a village whose name appealed to me. I saw "Kleinschweinbarth" - that would do. On satellite images, I could see every farm in detail, and I picked one surrounded by a generous stretch of grass where I might pitch my tent.

I drove there, rang the bell, introduced myself, and told my story. The old farmer was sympathetic to my project. I said, "Ich hab kaum Geld, aber große Träume," and he replied, "Wo ein Wille ist, ist ein Weg." Then I asked, "Also, darf ich bitte einige Tage auf Ihrem Land bleiben?" and he said, "Juah, ist mir egal." Herr Stampfer had been retired for twenty years and spent his days caring for his ill wife. He was glad for some help with the chores around the house. I fell into a rhythm I hadn't known since living at home: breakfast at eight, lunch at half past twelve, dinner at half past seven. For not only was I allowed to camp on their land, I was also invited to eat with them three times a day. That whole week, I was either working with my hands, editing videos, or visiting prehistoric museums. I was an hour's drive from Vienna, Brno, and Bratislava, exactly where I had wanted to be.

Before my visit to Vienna, I had contacted the Naturhistorische Museum Wien (NHMW), housed in a gigantic building commissioned by the Habsburgs [CP1] in the 19th century. It is also the permanent home of the figurine known as the Venus of Willendorf. Dr. Caroline Posch, curator and researcher in the Department of Prehistory, received me and we spoke with great enthusiasm about what it means to make a scientifically accurate film. What made the conversation particularly enjoyable was that she wasn't only an expert on the Stone Age — she had also seen a fair number of prehistoric-themed films. This meant we could exchange references within this strange little micro-genre. Below are a few reflections from that conversation.

Translating scientific knowledge into film is complex, since films make very different kinds of truth claims than scientists do in academic writing. An archaeologist develops broad theories and can leave room for possibilities. Take, for instance, the conclusions drawn from a typical excavation. An excavation yields so-called occupation layers: successive deposits of soil, bones, and, sometimes, human remains. In caves, such layers can accumulate several meters deep. After all the digging, sieving, and analysing, an archaeologist might conclude something like: for 20,000 years, various groups of people lived here; their diet first consisted of a certain percentage of meat, and later more fish; and the later groups made different tools than the earlier ones. The flint they used came from far away, suggesting that they either had trade networks or travelled long distances themselves. The excavation may also feed into a broader theory — one that combines findings from many sites to reconstruct human evolution as a whole. From that synthesis might emerge a claim such as: humankind evolved in a particular region of Africa into a form much like we are today, and over the past 300,000 years, spread across all continents.

A feature film, by contrast, doesn't show broad or analytical theories — it depicts specific, concrete events. Instead of learning that a population's diet consisted of a certain percentage of meat, we see people eat meat a few times. And by telling the story of one person, a film does not claim to represent how people on average lived over the thousand years before or after. Rather than oceans of time, the narrative shows a slice of it.

Moreover, a film must visualize many things whose existence we cannot be completely certain of. Think of it: a film includes all sorts of elements that never appear in Palaeolithic excavations — social interactions, clothing, body paint, language. Yet all of these are necessary to create a living whole. In doing so, the film steps outside the grids of the scientific method. In some ways, this mirrors the challenges faced by museums.

Dr. Posch took me through the museum's new permanent showroom, Kinder in der Eiszeit (Children in the Ice Age). The subject deserves special attention. One limitation of the archaeological record (that is, the set of material remains that survive well enough for archaeologists to find) is that the physical remains of children are less well preserved than those of adults. Children's bones are smaller and more porous, making them more susceptible to decay and erosion. As a result, we find fewer of them - and our image of Ice Age populations skews heavily toward adults.

Yet if we look at birth and death rates, and at the composition of more recent hunter-gatherer societies, a Late Palaeolithic group probably consisted of 40–60% children. Quite a contrast with our modern world, where you only encounter such ratios when a kindergarten class walks by. The exhibition was accordingly full of lively illustrations, Ice Age landscapes teeming with mischievous, laughing children. The displays itself were, appropriately, designed largely for young visitors. The curators had carefully studied what children enjoy in a museum, namely by organizing three workshops in which they simply asked them what they'd like to see. One of the top requests was a moving mammoth, though sadly that proved unfeasible. They were also curious as to the hygiene and toilet practices in the Stone Age. Otherwise, the children wanted to be able to touch things, climb on things, and sit on things. The exhibition provided ample opportunities for all of that — and, believing firmly in keeping one's inner child alive, I tried them all out during the tour.

What a contrast to the room next door, where the permanent prehistory exhibition stands. This gallery is under a kind of heritage protection, meaning that its appearance, purpose, and layout cannot deviate from the original Habsburg design. The result: dark green floral wallpaper, pompous old-fashioned paintings on the walls, and wooden cabinets filled with objects and neatly labelled cards. Fortunately, the current team is still allowed to update the contents of those cabinets. So, within this old-fashioned frame, we can still encounter modern science — albeit dressed in antique decor.

From this 19th-century room, you step into a smaller, separate space, you could almost call it a niche or chapel. Here, two world-famous figurines are displayed. Some scholars prefer to use the term female figurines, since the word chosen by earlier archaeologists has the unfortunate tendency to shape our interpretation. The Venus of Willendorf. The associations our culture attaches to that word are perhaps best embodied in Wagner's Tannhäuser, which I saw that evening from a standing spot at the back of the balcony in the Vienna State Opera. There, the tragic hero Tannhäuser is bound to a voluptuous goddess of a Venus whose sensuality is cast in moral contrast to the purity of a Christian court. When I viewed the figurine through this lens, hovering in the darkness behind the glass, her full, rounded shapes seemed like symbols of fertility. A fertility that, much like in Wagner, seemed to call out to me.

The term female figurine seems, at first glance, less prone to these Romantic associations. More formal, more technical. Yet even this phrasing brings its own colouring, now tied to the broader concept of "woman." The term confronts us with the need to ask what woman means, and what it might have meant to the cultures that, for tens of thousands of years, from western France to eastern Siberia, created these figures. Viewed through that lens, I understood that the Willendorf figurine belonged to a complete cultural system, used in rituals I will never understand, not only because they are irretrievably lost to time, but also because they were never meant for my gender. At least, that is my interpretation. There are about forty theories regarding the possible meaning of these Stone Age figurines, yet none can point to definitive proof of their precise use. Were they worn as amulets by young women to aid conception? Part of an initiation rite? Displayed on a column for worship, like in Roman times? Used as teaching tools? As toys? The answer, ultimately, is left to the reader.

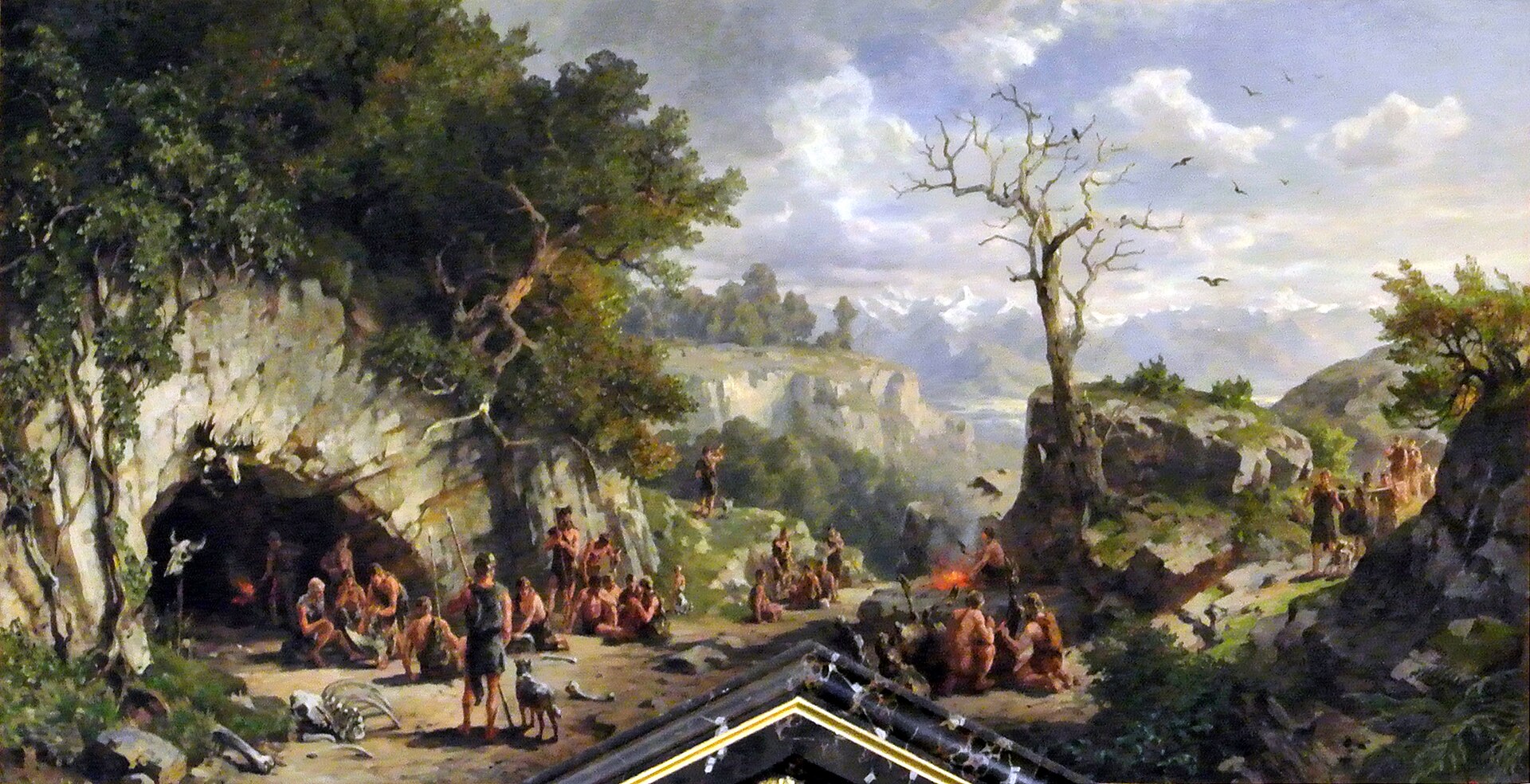

Interpreting findings — and deciding how to present them to the public — is one of the central challenges in curating archaeological exhibitions. At every museum I visited on this journey, archaeologists explained that they always have to "add things" where certainty runs out. Dr. Posch's team, for instance, had commissioned graphic reconstructions of a prehistoric tent. The goal was to show visitors how people might have lived. The illustration was based on an archaeological site: traces of a fire, surrounded by holes where posts had probably stood. "In this image," Posch said, "everything you see above ground is a stretch." The artists had been asked to draw a technical map of the structural design of a tent, which in the end was transformed into a cozy portrait of daily 'indoor' activities. Although the activities and their positions are based on archaeological data, it has to remain unclear whether the actual tent really looked that comfortable — in design or atmosphere. Speculation, then. But for an exhibition, that's not a bad thing. Petr Neruda, an archaeologist at the Moravian Museum in Brno, told me that such creative filling-in is necessary to tell a story that the public can connect with. Over a coffee table with Neanderthal points made of mountain crystal, he remarked that scientists build their theories with arguments — but people don't go to museums for arguments. At the Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte in Halle, the management believes an exhibition should be an experience. There, flint axes hang on the wall like a rain shower, and an elephant strides into the gallery a bit further down. The curators at the National Museum of Slovenia in Ljubljana would surely agree. Conservator Peter Turk showed me their exhibition on the Divje Babe flute. Some scientists, somewhat haughtily, doubt whether this 50–60,000-year-old Neanderthal object is truly a flute — but visitors can, in the meantime, play little tunes on a replica themselves.

Before leaving for the beautiful city of Ljubljana, I had made one more stop — in the attic of the Slovak National Museum in Bratislava. Their Palaeolithic collection was small, and most of the permanent pieces had been lent out to an exhibition in the castle on the hill above town. Unfortunately, that exhibition was closed that day due to a political event. So the director — who was not himself a Stone Age specialist — arranged for me to have a look in the storage area. What remained there were only a few boxes of unidentified white and brown flint fragments, gathered long ago by a farmer while ploughing his field. But the setting in which these pieces rested I simply found magnificent. Antique wooden beams arched high above rows of metal cabinets, their labels still typed on paper slips from an old typewriter. On the bookshelves stood genuine Neolithic pots filled with dried flowers, and from beneath a storage rack, the authentic marble head of a Roman emperor gazed upward from a cardboard box. Prehistory waited here among the dust, still in search of a story.

As I write this, I am already in the Alps, where, during a stop in the Ötztal, I finally found time to work on this blog. With my head still brimming with experiences I am already beginning the next phase of this remarkable journey.

September / October 2025