8. Circling Around the Alps

These past weeks the project really started gathering momentum. Not only did I visit more museums and come up with new ideas for the story of the next film, I was also increasingly approached by people in the field who wanted to collaborate. My first goal was Northern Italy. In Bolzano I could see Ötzi the Iceman, a legendary discovery that has permanently changed our view of prehistory. Two archaeologists from the Stuttgart region had also contacted me, and it was no problem for me to make a small detour to southern Germany.

Before driving through the Alps, however, I first settled for a bit in the countryside near Parma. Through a friend I had been invited by a Dutch couple who the year before had bought a house in the tiny village of Vigolo Marchese. A big, crumbling building that they were lovingly restoring themselves, beautifully situated between light-brown crop fields and friendly little villages. There was no running water yet, so every day they fetched water in buckets from a spring in the hill next to the house. Two young kittens would always come to nuzzle them, and in the attic some dog-eared French dime novels of the previous owners still lay about. The plaster was aesthetically peeling from the walls. Here, bread was more important than the job you earned it with. I found it magically beautiful to be there. Their plan was to start an artists' community in the future, and film projections with my cinema kit could certainly become part of it. During my days there we gradually became not just friends of friends, but simply friends. Experiences like this are what make travel such a wonderful phenomenon for me.

Before going to see Ötzi's remains, I first wanted to have a real Ötzi experience. To camp in the Alps—in the Ötztal, to be precise—not far from where our famous friend from the Early Copper Age was found. It was already October, but I had a good winter coat and a thick blanket, and I wasn't afraid of anything. Alright, in the end I just stayed at a campsite, but it lay directly between wild mountain walls, practically in the middle of nature. The water from the taps here came straight from the mountain stream. And at night it really froze. Frost formed on my car, my tablecloth became rigid with ice, and in the morning I had to thaw my iron frying pan before I could fry eggs in it. I enjoyed it frankly. Each day, the sun would slowly creep up behind the mountains, and as soon as the light hit my spot I could take off my winter coat, sometimes even my wool sweater. Then I could head out. To see the mountain peaks Ötzi had seen, to drink from a spring that already flowed in his time. To become out of breath from a climb as he did in his final hours. The surroundings gave me ideas and I wrote a lot.

At the moment I have the idea to center my next film around a woman's second pregnancy. Firstly, the female form is very often depicted in Ice Age art. Second, giving birth to a child lies at the core of the circle of life; it is also a severely underexposed aspect of life in prehistory, as is childhood (see blog 7). Moreover, a pregnancy of nine months fits nicely into the framework of the four seasons: three seasons of carrying, and one season of building up to that. There will also be a hunting scene, which brings the aspect of death to the story - the other side of the circle of life (see also my thesis). These are all still early ideas, so please pin me down for them, but if you have suggestions feel free to get in touch.

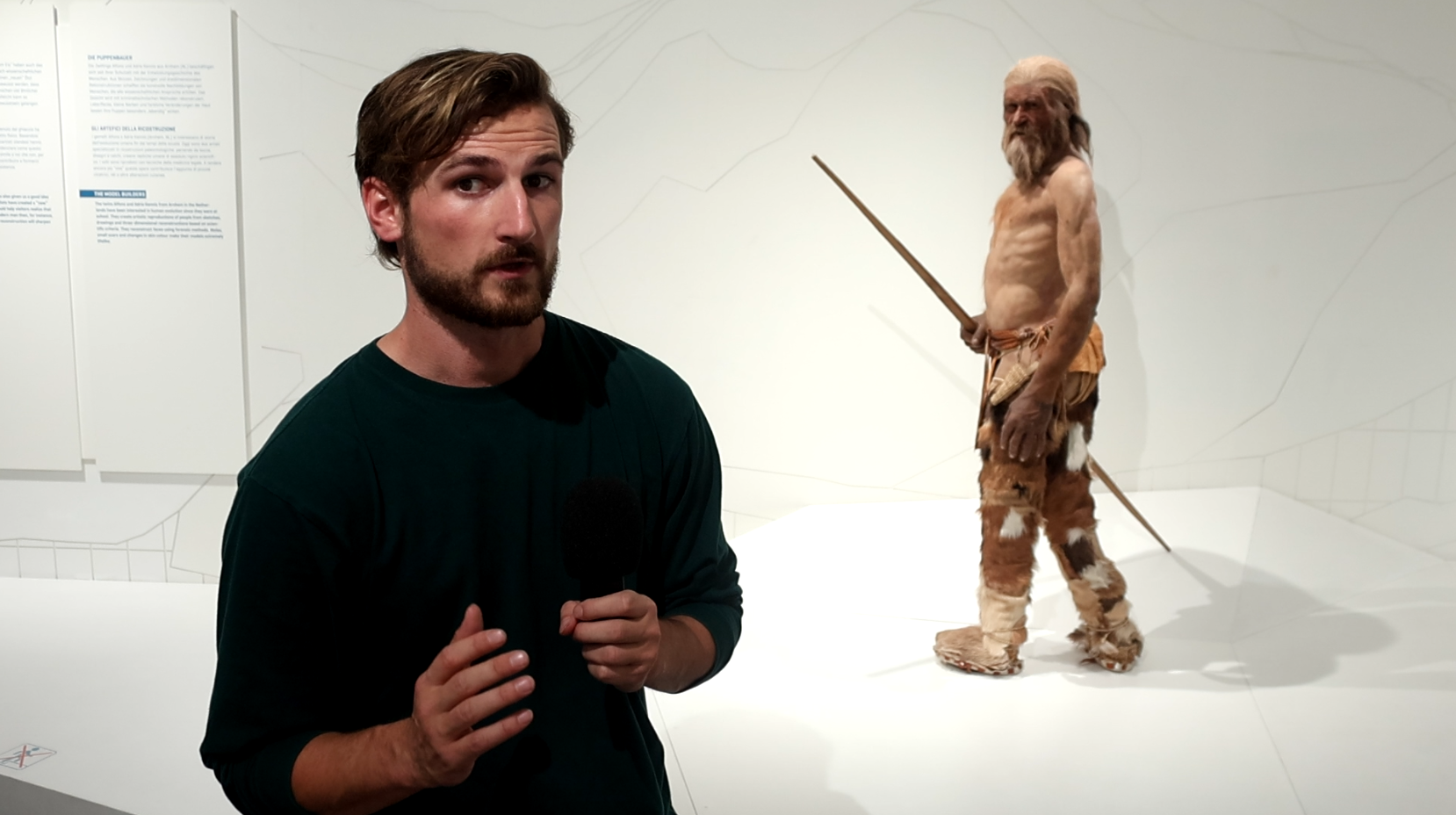

After my mid-October camping weekend came my appointment at the South Tyrol Archaeological Museum, where Ötzi's body and his belongings are exhibited and studied. The museum is housed in Bolzano, a beautiful baroque city nestled among the mountains. Remarkably, on the street you hear as much German as Italian. This bilingualism is best illustrated by how I ordered my coffee in Café Mozart: "Ein Espresso bitte." The museum treated me to a tour, and my guide told me all sorts of interesting details about their unique find. The story has become nearly mythical by now. In the 1990s hikers saw a corpse sticking out of the ice of the Similaun glacier. They thought it was a hiker, and the extraction of the body was in the beginning anything but careful. But this man from the ice turned out to be a time traveler from 5,400 years ago. An ice mummy of a tough middle-aged guy who suffered from arthritis and parasites but nonetheless climbed the Alps. Stripe-shaped tattoos across his sinewy body. And he had a copper axe that, in today's money, would cost about as much as a Ferrari. He formed a unique time capsule from a long-lost and mysterious era in which this metal made its entry into Europe and the so-called warrior culture emerged. An arrow in his shoulder had ended his life. It also seemed that some of his arrows had been stolen. All this is why he is so famous: he was an ancient badass.

But the Copper Age is almost postmodern compared to my period (the Late Stone Age, i.e. 40–11 thousand years ago). So why did I go to Bolzano? Some of the museum staff also had their doubts during our meeting. The thing is, Ötzi wore clothing and carried many other objects that still strongly resemble Stone Age materials. Sewn leather, woven plant fibers, a birch-bark box, and a flint knife. Remnants from an earlier time that still worked perfectly well. A bit like how we still use vinyl records to listen to music, or a fountain pen to write. Just like we have not yet entered the digital age for 100%, Ötzi was not a man solely of copper. Only his axe brings him into the Copper Age. In other words: as far as he had soft materials, he offers a trove of information about how people made objects not just in his period but before it as well. His trousers and shoes are the oldest pieces of clothing in the world, and since they were discovered, almost all experimental archaeologists make their clothing based on this model. The trousers my actors wore in The Bison's Legs, made by Lucia Ros and Diederik Pomstra, were also based on these. The museum staff were eventually happy to support me.

After my visit to Bolzano I traveled further north. Two archaeologists in the Stuttgart region had contacted me about a potential collaboration. The organizers of the archaeological network EXARC had promoted my project a lot, and through their channels they had read about it. I am very grateful to EXARC, because since then I regularly receive emails from researchers and artists who want to help with the project. A Dutch archaeologist doing her PhD research on cave art, a Spanish illustrator of archaeological papers and children's books, and a Swedish archaeologist-filmmaker, just to name a few. Because of this I am increasingly confident that I can secure a serious budget and get the production underway. In any case, I had a good reason to make a detour from my planned route, and I spent about a week in southern Germany. I was able to stay with a friend of my father's in the village of Spaichingen. With six dogs, six cats, and all the children still at home (or around the corner), it was a lively crowd.

The region is also known as Swabia. Where southern France has cave paintings, here they have musical instruments and figurines. Although the caves of Swabia would have been perfectly suitable for drawings, people apparently made a long-term choice not to. Instead, they made musical instruments and figurines out of bone and mammoth ivory. Of the musical culture a few fascinating flutes remain. These, at about 40,000 years old, are the oldest musical instruments in the world (if we do not count the Divje Babe flute). People probably played on other instruments as well, but those have not been found. These flutes were one of the inspirations for The Bison's Legs and are exhibited in the Prehistory Museum of Blaubeuren. Earlier this year I visited this museum and presented my film there. For anyone who had not yet seen it, I made this video about the visit:

This time I visited the university museum in Tübingen. In this medieval city they conduct leading archaeological research, and I hoped to get in touch with the scientists. My attempt, however, turned into a Kafkaesque experience. First, they did not respond to my emails, and the phone numbers I could find did not work. My plan then was, just like I was going to do in France, to simply show up and pester people until I could speak to someone. The address of the archaeology department was online, so that became the first stop. I could walk in just like that; there was no reception desk but there was a map with the layout of all the offices. They were on a hallway on the top floor. Once upstairs I saw no nameplates on the doors, and all the doors were locked. The floor below, same story. But on the floor below that I found one researcher working at her desk. It turned out that today was the day of the Master's thesis defenses. Moreover, the people I was looking for had moved five years ago to the castle on the hill. Oof—if you've read Kafka, you can already feel it coming.

After a walk through the winding streets of Tübingen's old center I finally reached the castle. Some branches of the University were housed there, as well as the archaeological museum. But no indication of where the archaeologists were. At the museum desk they told me I had to go through a gate at the inner courtyard, up a small staircase, and then a bit further. I ended up on the castle walls, where an apple tree was basking in the sun, and then entered a small house where the Sociology department turned out to be. A woman told me I had to go up another staircase, which went against the outer wall of the main building, and that I should knock on the door. No answer. That was all there was to it. I decided to pick an apple. The Sociology woman felt sorry for me while she was smoking outside, and we talked for a while about my project; she turned out to be interested in the Stone Age as well. That was the extent of my contact with Tübingen.

Luckily the museum had some breathtaking finds. Ten figurines of bone and mammoth ivory—unfathomable little artworks that confront us with the deep gap in time between us and their creation. In a darkened room behind glass floated a lion, a fragment of a bison, a few mammoths. A few works so worn that the animal was no longer recognizable. And a horse, carved so beautifully that it brought tears to my eyes. I can hardly explain the feeling. It was one of those moments where nostalgia, curiosity, and a glimpse of undeniable humanity took hold of me. I feel this every time with such finds. It sparks the flame in me that drives this project. I thought that this horse might have been the toy of a child 40,000 years ago—a child who played with it as I once played with my toys. But perhaps it was used for something completely different. It is up to us to interpret it.

The next day I went to Bregenz for the first interview, with Laurens Thaler. Officially he is not yet an archaeologist, but at age nineteen he was already so deeply involved with the subject that in essence he already was one. Not only did he have a collection of self-made spears, knives, bags and headdresses from all sorts of periods; he had also made a complete Ötzi outfit and had all of Ötzi's tattoos put on his body. That's what I call dedication. Laurens showed me his favorite place, a river where, in a certain bend, you get a view that can be called 'pure nature.' No human-made things spoil the view of the mountains and the round stones of the riverbed. In full Ötzi attire he told me about his passion for the past and about the disturbed balance between humans and nature. Where humans once lived in a kind of harmony, we now devour the planet and pollute her. The whole development since the Neolithic seems a major mistake, and the Industrial Revolution the nail in the coffin. In this worldview—shared, I believe, by many—humanity, insofar as it builds cities and digs mines, damages nature. Only the lifestyle of hunter-gatherers is truly sustainable. Archaeology, and bringing the past to life by replicating and using artifacts, was for Laurens the way to connect with this past situation. For our society it remains to be seen whether we can find a balance.

I try to remain more positive. Major problems are certainly coming, given the changing climate, but if the past teaches us anything, it is that our species is very flexible. Time and again societies have adapted to new environments and changing circumstances. Human inventiveness is great—and keeps growing. Although the industrial-agricultural complex will not cease to exist, it is not unthinkable that its impact will be minimized. We will have to. Perhaps over time we can live in a way that resembles hunter-gatherers: by using only materials that decay or that cause no harm when they end up in the environment. By giving something back to nature each time we take something. I hope my next film can contribute positively to these developments, by conveying a message about the original relationship between humans and nature. By the way, Laurens himself did not come across as cynical at all. He was bursting with enthusiasm. He wanted to leave Bregenz as soon as possible and, after a gap year in Southeast Asia, study archaeology in Vienna with Dr. Caroline Posch (see blog 7).

The second interview was with Markus Klek, a German experimental archaeologist with already an entire career in the field. Instead of one room, half his house was full of prehistoric items. Richly decorated parkas, drums, axes, spears, bows—you name it. I felt like a kid in a candy store. Markus went further than most people with his creations. Not only did he make Stone Age gear, he also went trekking through the Alps with it. Really sleeping and surviving as they did back then, and seeing what you can learn. He recently told a number of wild stories about his latest trek in an EXARC podcast.

With Markus, I also had long and interesting conversations. What stuck with me most were his ideas about shamanism. Making objects and surviving with Stone Age gear is one thing, but adopting the spiritual mindset of hunter-gatherers is another matter entirely. I asked about a drum hanging on the wall, and whether it was a shamanistic drum. "I'm careful when it comes to these sorts of shamanistic things. When I was younger, I was looking for an authentic shamanistic way to follow here in Europe. But it was impossible," he told me. People's attempts here just came across as fake. "There are no traditions. People just make awful mixtures of Native American and Celtic cultures and all sorts of stuff." The term "shaman," by the way, originally applied only to a few traditional cultures in Siberia; gradually it has become a general term. Other Indigenous cultures prefer to use their own words. In Arizona, for example, I learned that the Navajo prefer the term "medicine man," and I read that in Arnhem Land (Australia) Aboriginal groups speak of "those who know." Yet the term shamanism stuck and is often used to describe spiritual figures in widely different cultures. And as noted, a handful of European hippies have also claimed the name. Because authentic traditions were lacking in his surroundings, Markus sought his own path. He arrived at a minimalist approach "without hocus pocus. I don't claim to follow any sort of tradition." He only needs a drum. We exchanged ideas for hours, and he was very eager to help with the project. Both my interview with Markus and with Laurens were the kind of encounters that make this Grand Tour so wonderful.

The southern German adventure then came to an end. I was very grateful to my host family for the coziness and the strong stories. I headed south again, through the Brenner Pass back to the Po Valley, where I spent another week with my friends in Vigolo Marchese. Here I found time to reflect and to edit videos. I was at the midpoint of my journey—I had driven about 9,000 kilometers in that old Ford of mine. I had visited Germany, Italy, and Eastern Europe, and got six museums on board. Now I had almost two months for France and Spain. It would be warmer there, but also more challenging. The French did not respond to my emails, nor did the Spanish. That is why I needed all that time for this second part of the journey. And in Marseille my camera would be stolen. But that is a story for the next blog.

October 2025