9. The French Connection

In France I experienced an incredible number of adventures. I stayed there for more than a month, in one of the regions with the highest concentration of Palaeolithic caves in the world. Above all, I found a great deal of inspiration, made many friends, and saw an enormous number of Ice Age artworks. Here, I was able to look at prehistory through French eyes.

But there were also plenty of difficulties. Experts elsewhere in Europe had already warned me that the French can be quite difficult to deal with. And to be fair, they do have a lot to be proud of. One hundred and fifty years of uninterrupted archaeology makes France the most extensively studied region in the world, with Stone Age sites ranging from Homo erectus all the way to the Neolithic. On top of that, they possess world-famous decorated caves such as Lascaux and Chauvet. It is not an exaggeration to say that this has given the French a kind of collective obsession with prehistory. As a result, scientists and museums can come across as a bit hautaine, and approaching museums turned out to be slightly Kafkaesque.

For comparison, consider that in all other European countries, museums were immediately open to my visit after a single email, welcoming me for conversations and sometimes even guided tours. Not in France. I had contacted around ten museums and never received a response. Pas du tout. And when I would call, the response would be: "Oh, interesting, just send an email and we'll look into it." The clichés seemed to be confirmed. Still, I had some hope: I speak a decent amount of French. I suspected the institutional approach would remain stiff, but that face-to-face things might be easier, perhaps after a glass of wine or two. My plan was simply to show up everywhere and stay at the reception desks until I could speak to someone.

My first stop was Marseille. Normally I would never go there because of all the stories about crime, but I decided to take the risk because of a remarkable museum: Cosquer Méditerranée, the replica of the Cosquer Cave. My hair still stands on end when I think about the discovery of this cave. Its entrance lies 37 meters below sea level, along the coast near Marseille. During the Ice Age, the sea level was about 100 meters lower, and the coastline lay 8 kilometers farther out. After many attempts, the diver Henri Cosquer found a way through the flooded passages and, at the very end, climbed 37 meters upward into a chamber, with air still inside… and filled with cave art. Horses, penguins, hand stencils. More than 500 figures have been discovered in the dry section alone, implying that the cave may originally have contained thousands of images. On a rock still lay an oyster shell that had been used as a grease lamp. This was definitely a museum worth visiting.

Full of optimism, I approached the front desk and later even managed to call someone from the communications team, but it went no further than: "Sounds nice, leave your email address and we'll look into it." Too bad. But then again, my film isn't called The Penguin's Legs. And fortunately, the replica itself was beautiful.

What was less fortunate was that the next morning my car had been broken into. It was parked in a garage that could only be accessed with a code, but that hadn't stopped the thieves. They probably saw the large speaker I used for my mobile cinema, smashed a window, and took it. Along with my backpack and my entire camera kit. More than €2,000 worth of equipment, and unfortunately, I wasn't insured. It was devastating, and I was badly shaken. I was now a filmmaker without a camera.

The thieves did show a strange kind of consideration: they had thrown my sweaters and T-shirts out of the backpack, probably to make room for the speaker. However, they did take my underwear and socks.

I was deeply saddened by this, but I quickly decided not to wallow in misery. That same morning I drove to the Ardèche, to the Chauvet2 museum. For two years I had been trying to reach them, since my film was inspired by their cave and because I wanted to collaborate with their experts on a future film. In the car I put on my neat outfit: a blue linen jacket, corduroy trousers, and brown leather shoes, though still wearing yesterday's socks. The others had been stolen.

At the front desk they suggested I leave my email address, but no, that wasn't an option today. The head of the desk was called over and took me to someone walking through the exhibition, who then brought me to the people running the replica. That was the Chauvet2 hierarchy. One that, I discovered, seems to disappear once you've climbed its steps. Once you're at their level, people are incredibly friendly. The team—three people—were, after my nervous French explanation, willing to let me screen my film in their office. They thought it was bizarre that I had never heard back from my messages. Exciting! And it was received wonderfully. My film aligned perfectly with how the museum wanted to present prehistory: without violence, with a touch of humor, and suitable for the whole family. They appreciated my careful attention to archaeology and the clear place given to science. They promised to do their best to promote the film to the management, and perhaps it might eventually find a place in the museum.

I don't often experience emotional rollercoasters like that: from a serious break-in to artistic recognition in a single day. As if that weren't enough, four friends of mine happened to arrive in the Ardèche that evening, where we had rented a small house for five days. I was on the way up again. I'm still waiting (January '26) for a final answer from Chauvet2, but I knew I had done everything I possibly could to bring my project to their attention. And I would simply continue the journey. I could still drive my car, I still had some money, and museums were still willing to work with me. I wasn't about to be stopped.

After the Ardèche, one friend stayed on while the others returned to the Netherlands. The two of us went to the Dordogne, a region where the roadside is covered with signs announcing prehistoric sites. It is one of the areas with the highest concentration of decorated prehistoric caves in the world. And, importantly, you can still visit several of them in their original state. Not replicas (though Lascaux IV is impressive too), but real authentic engravings and animal paintings made many thousands of years ago.

In just a few days we visited the phenomenal caves of Les Combarelles, Bernifal, Font-de-Gaume, the relief of Cap Blanc, and the magnificent collection of the National Museum of Prehistory in Les Eyzies. Every time I stand before an authentic work of Paleolithic art, I have a mystical experience. That may sound exaggerated, but it's the best way I can describe it. I feel as if I'm standing before vast oceans of time separating me from the person who made the work. And at the same time confronted with its beauty, refinement, and craftsmanship. I'm struck by the undeniable humanity of an era forever lost and unreachable. During my time in France, I was fortunate enough to experience this several times a week. The cave that moved me most deeply was Pech Merle, both the drawings and the geology. I cannot put it into words.

My friend returned home, where (also inspired) he began devouring books on prehistory with great enthusiasm. We had been sleeping in a plastic chalet, but I didn't even have the budget to continue doing that for the rest of the trip. So once again I went in search of a farmer where I could pitch my tent (see blog 7). I hoped to stay near Les Eyzies so I could visit the museum every day and walk to buy a baguette in the morning.

The first farmer I found via Google Maps satellite images only offered a patch of grasswithout a shower or toilet. Not ideal. The second door I knocked on turned out not to be a farm at all, but the home of a retired couple with a huge garden. They were Pierrot and Gizelle, incredibly kind and hospitable people who had long been hosting all sorts of residents on their land. In summer, friends of friends often came for seasonal work. As permanent residents, a Dutch man lived in a wooden cabin, their grandson in a studio, a woman in a caravan, and a documentary filmmaker in a yurt. When I explained why I was in Les Eyzies, they immediately agreed that I could stay on their property. They even offered me their grandson's van. Which, given the rain and freezing temperatures of November in the Dordogne, admittedly was far more comfortable than my tent. As elsewhere in Europe, I was once again deeply touched by people's generosity and hospitality. I was a twenty-minute walk from the national museum. I no longer had a camera, but my wanderlust was greater than ever.

I spent more than a month in Les Eyzies. I grew attached to its few streets, the beautifully eroded rock faces, and the mist drifting in from the river through the quiet lanes. The low season had just begun. Nearly all restaurants were closed, and Les Eyzies became what it had secretly always been: a sleepy French village with a bakery, a butcher, a grimy tobacco place, and one or two bars. I spent countless hours writing in the Pôle International, a media center dedicated to the study of prehistory. Often, I was the only visitor.

Although not all caves were open during the low season, this period had the advantage that people in the field had more time. It was time to network. I gave everyone I spoke to my website and email address - at museums, caves, cafés - and everywhere the response was extremely positive. People found the project interesting and kept introducing me to new contacts. A guide I met at Cap Blanc was so enthusiastic that she emailed everyone in her organization, and within a week I was sitting at the table with monsieur l'administrateur of the Centre des Monuments Nationaux.

The National Museum of Prehistory was harder to reach. I tried for two weeks to set up a meeting, but my contact didn't respond. This time, though, I had patience, and Les Eyzies turned out not to be very big. Through various connections I met the musician Pascal Saiga (@passeur_de_notes), who organizes interactive prehistoric music sessions for the public. We had a few beers at Le Syana, the café opposite the national museum. He recognized some people at nearby tables, and sure enough, my contact was sitting there. The next morning I was at her desk. The French museum world had seemed so closed at first, but indeed, once I was there and sharing a glass of wine, it wasn't so bad at all.

During my month in the Dordogne I spoke with a great many people: archaeologists, professors, guides, often over coffee or a few beers. Notably also éminences grises like Serge Maury and Jean-Michel Geneste, who both welcomed me into their homes one evening with homemade vin de noix for philosophical discussions about making Stone Age films. Or professor Francesco d'Errico, who received me at the University of Bordeaux and gave me a personal lecture on everything he knew about fertility in prehistory. Someone's partner turned out to be an anthropologist who, over coffee at the market, told me about her research on shamans in Tibet. And so on.

One of the most remarkable encounters happened in the village of Le Buisson. My old Ford Mondeo needed new tires, and while waiting I sat drinking coffee at restaurant La Symphonie, the kind of place where everyone greets the bartender and usually knows a few people inside. I was reading when a local drove straight into a sidewalk post outside the door. He walked in and ordered une pression as if nothing had happened. I soon struck up a conversation with the person next to me, who asked what I was doing in the area. When I explained I was making a film about prehistoric cave art, an elderly man two tables away spoke up: "Oh, but I have a cave!"

He turned out to be none other than Marquis Hubert de Commarque, local aristocrat and owner of the Grotte de Commarque. This small but remarkable site lies beneath the ruins of a medieval castle of the same name and is no longer open to the public. Quelle coïncidence! I immediately seized the opportunity. I showed a few minutes of my film on my phone, explained my project, and mentioned that I'd be staying in the region for a few more weeks. Hubert, speaking in the thoughtful manner typical of the old elite, was enthusiastic. A visit to his cave should certainly be possible. After I met him, it took two weeks of phone calls, but by the end of November he told me I could come by. Two archaeologists would be working there the next day. Would I mind picking up the key and bringing it to the cave the following day? He himself didn't have time. Why of course! And just like that, I spent a day walking around with the key to Commarque.

I arrived at the iconic castle via crumbling chemins. As rain poured down outside, archaeologist Oscar Fuentes gave me a tour of this mysterious place. Only once, back in 1981, had the cave been seriously studied since the engravings were recognized in 1915. That was precisely why Oscar was working there: it was an almost forgotten cave, likely still hiding secrets. After a small chamber near the entrance, which was used as a dumping ground in medieval times, you enter a tunnel ending in a T-junction. To the left: a passage with nothing but a humorous pigeon someone must have drawn recently. To the right: several small, hard-to-interpret engravings. A small horse's head, perhaps a Gönnersdorf-type female silhouette...

We went back outside before reaching the highlight. Oscar wanted to check where his colleague was. No signal. So we went back in. At the back of the right-hand chamber: the horse. And not just some horse. A phenomenal bas-relief of a life-size horse, partly covered with calcite deposits but unmistakably a masterpiece. In terms of expression and realism, the head could have been carved in ancient Greece. Although several bas-reliefs from this period are known, this is the only one in the world created deep inside a cave. Truly unique.

To thank him for this extraordinary opportunity, I screened my film for the marquis. I picked him up at his enormous château, with its 13th-century towers, 16th-century tapestries, and a small cannon from the French Revolution (the Commarques must have survived that quite well, I thought). I set up my cinema at his daughter's château (yes, a separate one). Hubert and his family were enthusiastic, and when I dropped him off he remarked with a smile: "Tu as bien profité de cette situation, je crois!" All of that because I needed new tires and decided to sit in a café.

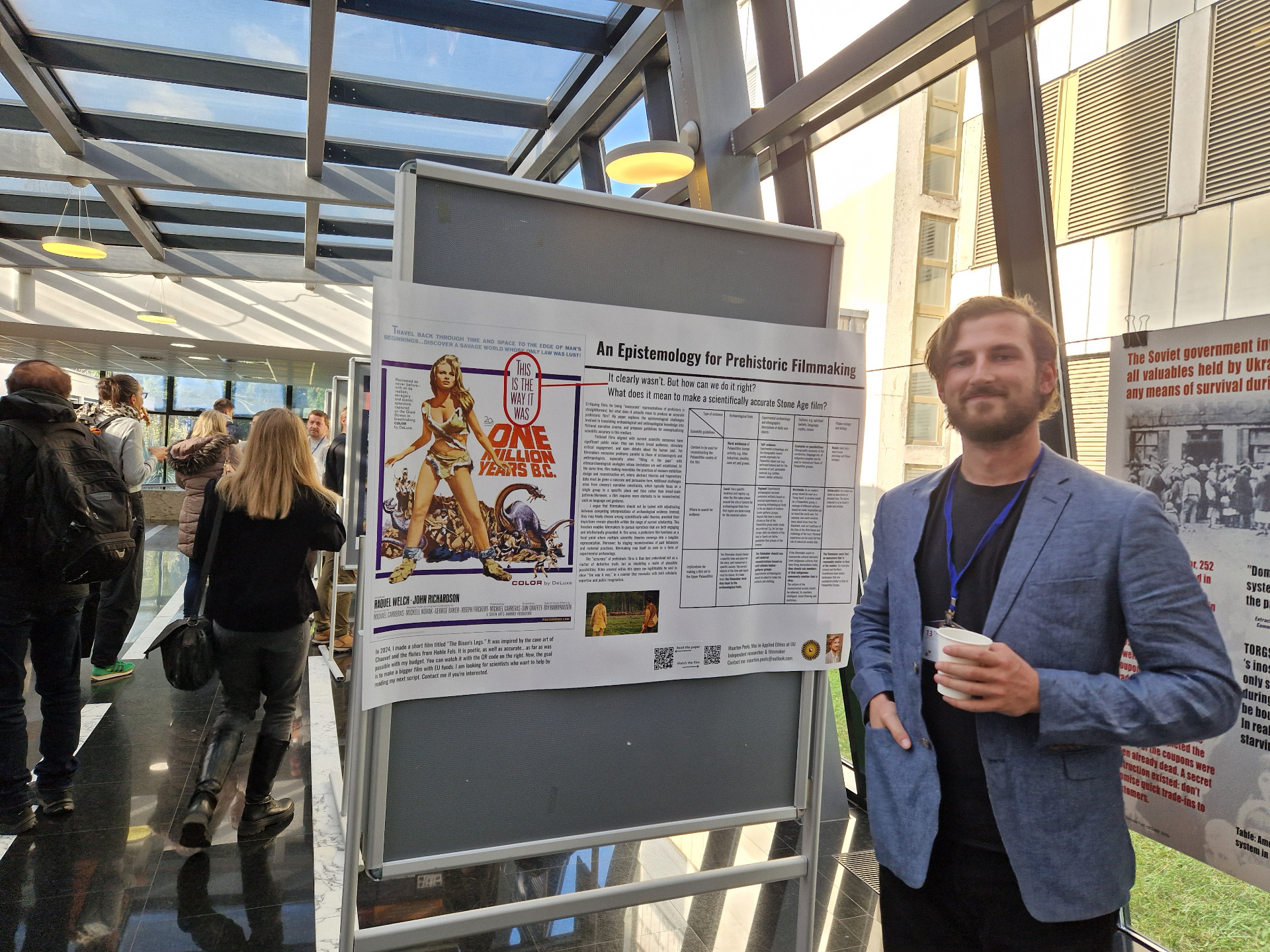

My time in France was then briefly interrupted: I had been accepted to the Methodology and Archeometry Conference (MetArh) in Zagreb, where I presented my ideas on prehistoric filmmaking. The title of my paper was This is what it was like: an epistemology for prehistoric filmmaking. In it, I explored how science can be incorporated into fictional film. Conversations with museum professionals, combined with my own experiences as a filmmaker and knowledge gained from books and articles, came together in this text. The idea was to philosophically examine what it means to be scientifically accurate in a fictional film. It is easy to point out mistakes in the average (pre)historical film: objects, animals, or actions that don't fit the period. But being truly accurate is far more complex. On the one hand, there are countless small details to consider; on the other, there are major gaps in our knowledge, especially for periods tens of thousands of years ago. Scientists also disagree on many issues. You can't please everyone. But you can try, and in my view the result of that effort greatly enhances both the aesthetics and the emotional impact on the viewer. Plenty of food for thought. You can read it all here.

I presented these ideas at the MetArh conference in the form of a striking poster (see below). I had to spend a substantial portion of my remaining budget on the plane ticket, but it was absolutely worth it. By participating in the conference and presenting my paper (even if only as a poster) I found myself within the scientific community. This was crucial for my project, as it gave it legitimacy. And the conference itself was wonderful: I made many great contacts, tasted delicious gemišt, and even screened my film for a group of archaeology students. I also had a great conversation with Katarina Šprem, who runs the archaeological organisation called PETRA (@udruga.petra)

Soon I flew back to the Dordogne, where I still had a few days to meet people before continuing my journey. In early December I went to the Pyrenees and, together with archaeologist Barbara Oosterwijk, visited the caves of Niaux and Gargas. Epic caves preserving the dreams of many generations of hunter-gatherers. At Niaux, an immense tunnel leads the visitor 500 meters into the mountain, ending in a cathedral-sized chamber where refined black animal drawings confront you with unanswerable questions about the past. At Gargas, a homely chamber covered in hand stencils opens onto an underground world of bizarre geological formations and enigmatic drawings. Those who undertook these journeys long ago left their handprints behind here as well, bearing witness to their sense of adventure.

And then, for the time being, the French chapter came to an end (I miss Les Eyzies so much that I'm returning in May). I still had a week in Cantabria ahead of me—the final stage of the Grand Tour Préhistorique. That story is for next time.

November-December 2025